December 4, 2024 - Vol. 17, Issue 50

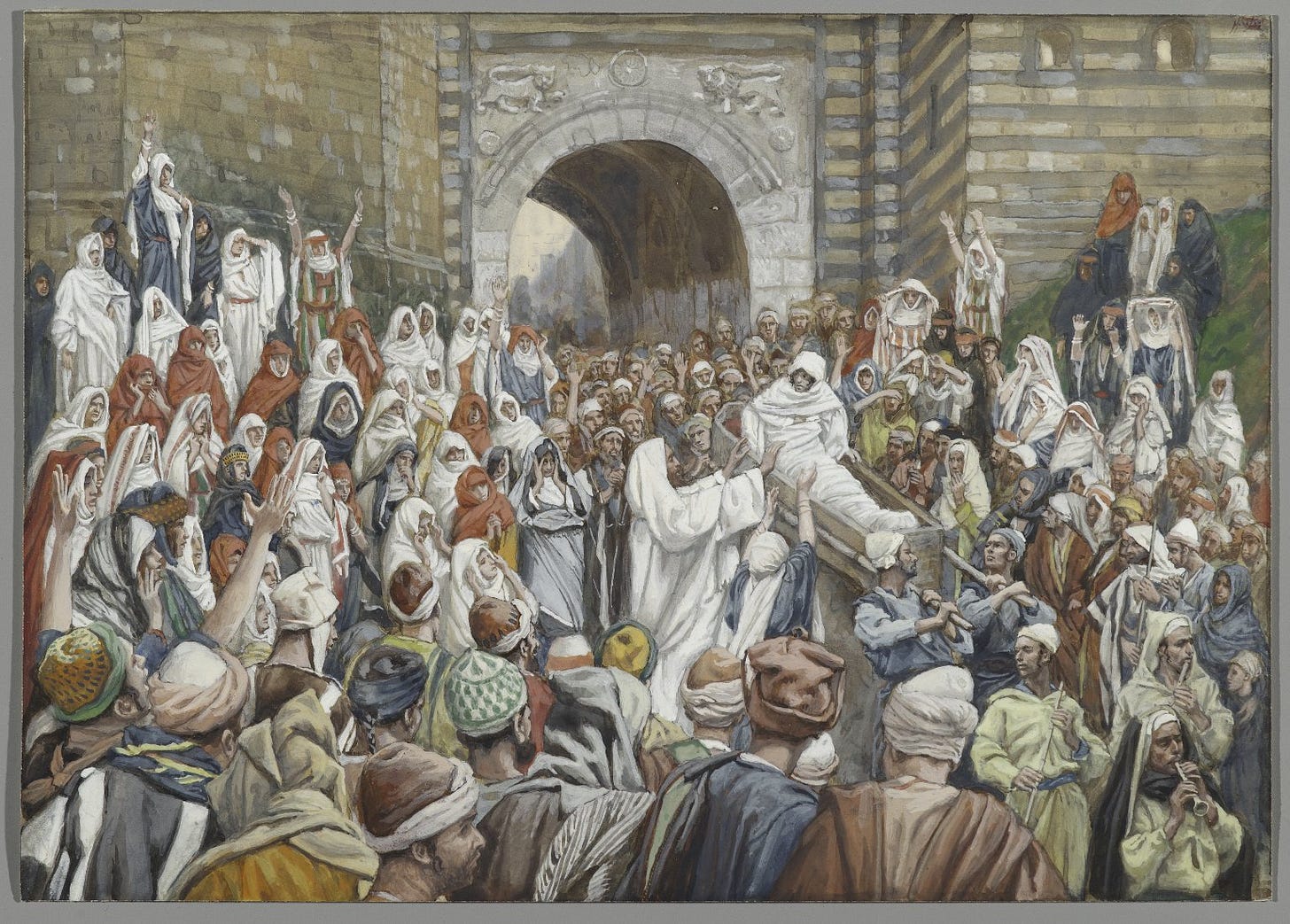

In the quiet village of Nain, grief was a familiar companion. A widow walked behind her son's funeral procession—her last and only connection to life, to hope, now being carried away on a wooden bier. In the brutal economics of first-century Judea, a widow without a son was a woman condemned to destitution, to invisibility.

But this was a moment when the universe would pause.

Jesus approached. Not as a distant deity, but as a human so deeply attuned to suffering that compassion was less a choice and more a breathing. He saw her. Not just saw—he felt her loss in a way that transcended mere observation.

"Do not weep," he said.

Three simple words that would become an extraordinary interruption.

He touched the funeral bier—an act that would have rendered him ceremonially unclean. But cleanliness was never the point. Compassion was. Connection was. Restoration was.

The young man sat up. Life returned. Hope walked again.

In our world of transactional interactions, of scrolling past human stories, of maintaining safe distances—this story demands we look differently. It suggests that mercy is not a distant concept, but a radical act of interruption. That compassion can resurrect what society has already declared dead.

Who are the widows in our modern processions? Whose hope has been carried away, declared finished? Where might we be called to interrupt, to touch, to restore?

This is the gospel—not as a set of rules, but as a living, breathing invitation to see deeper, to love wider.

Our modern processions look different, but the grief remains familiar.

We carry our losses quietly—jobs lost, relationships fractured, dreams abandoned. We move through crowded streets, invisible in our pain, believing our story has reached its final chapter. Society passes by, averting its gaze, uncomfortable with unscripted sorrow. Compassion lost.

But what if mercy is always closer than we imagine? What if compassion has a sound—not of grand pronouncements, but of a gentle, unexpected interruption?

In my own garden, I've watched how life persists. The rose that seemed dead through winter suddenly bursts with unexpected bloom. The kumquat tree, after months of seeming dormancy, produces fruit that catches the light. Nature knows something about resurrection that we often forget: endings are not always final.

The widow of Nain's story isn't just about a miraculous healing. It's about being seen. Truly seen. In a world of algorithmic connections and curated presentations, true seeing has become a rare art.

Last week, in that brief moment with the Costco bagger—a stranger who paused, who smiled, who connected—I experienced a micro-version of this biblical encounter. A moment of unexpected mercy. A small resurrection.

These moments are everywhere, if we have eyes to notice them.

But what happens when mercy demands more than a moment? When compassion requires us to carry the weight of another's story?